By Sharon Hill

What happened to the chain-rattling, stone-throwing, hair-raising physical manifestations of entities we used to hear about from the old days? Did the ghosts get lamer or is the changing face of paranormal activity a reflection of ourselves and our needs?

Today’s ghost hunters on weekend jaunts and on TV and seem to know very little of the long, convoluted, vibrant history of haunts and ghost lore. They would do well to pick up a copy of Roger Clarke’s A Natural History of Ghosts: 500 Years of Hunting for Proof (Penguin, 2012) and have a look at how ghosts have changed through time. A worthy companion to Finucane’s classic Ghosts: Appearances of the Dead and Cultural Transformation (Prometheus, 1996), this is a highly readable historical look at ghosts from a cultural perspective. You certainly don’t have to be a believer to enjoy it and learn along the way.

What happened to the chain-rattling, stone-throwing, hair-raising physical manifestations of entities we used to hear about from the old days? Did the ghosts get lamer or is the changing face of paranormal activity a reflection of ourselves and our needs?

Today’s ghost hunters on weekend jaunts and on TV and seem to know very little of the long, convoluted, vibrant history of haunts and ghost lore. They would do well to pick up a copy of Roger Clarke’s A Natural History of Ghosts: 500 Years of Hunting for Proof (Penguin, 2012) and have a look at how ghosts have changed through time. A worthy companion to Finucane’s classic Ghosts: Appearances of the Dead and Cultural Transformation (Prometheus, 1996), this is a highly readable historical look at ghosts from a cultural perspective. You certainly don’t have to be a believer to enjoy it and learn along the way.

Clarke, a British media critic for 20 years, outlines the eight varieties of ghosts categorized by the late Peter Underwood: elementals, poltergeists, traditional/historic ghosts, manifestation of mental imprints, crisis apparitions, time slip ghosts, phantasms of the living, and haunted inanimate objects. Who knew there were so many?

At points in time, each used to be an accepted idea of what a ghosts was. Since there is no scientific explanation for what people call a ghost, we can’t measure them (contrary to what the Go-go-gadget-wielding paranormal investigators say). A “ghost” is very much at the whim of cultural trends. “Ghost” has no good definition: it’s fluid and we humans can’t seem to pin the darn things down.

> Ghost FAQ: Facts and Fiction

Clarke relates that the medieval ghosts were moral harbingers. They warned the unfortunate victim of the haunt to mend their ways. The purposeful ghost of this type, Clarke says, is an “archaic model from Roman literature and ancient Greece”. The ghost was angry that traditional funerary rites were not conducted. The body of the ghost could be vaporous or lifelike with visible wounds of their death. (See Finucane, 1996)

In the 17th century, ghosts were thought to have been conjured by witchcraft; they were simulacra or demons masquerading as a former human. What goes around comes around, as we see this concept reappear in 21st century pop culture.

Back before television and camera phones, ghosts were described in dramatic accounts as full body apparitions that might be seen at noon as well as midnight. You didn’t have to wait until 3AM, the “devil’s” hour, or "go dark" to spot them. The famous Borley Rectory ghost, the nun, had her own "walk" where you could wait to see her appear at dusk.

In literature and the theatre, the ghost was handy to tell important aspects of the story. Clarke notes that in the 18th century, ghosts came around with something important to say about lost property or hidden wills. The classic Dickens’ ghost serves as a critical plot device and influenced our ideas about ghosts for a very long time as well as did Gothic fiction of MR James and Henry James.

Over and over appears the trope of the ghost who points to the location of his or her unceremoniously dumped remains. Ghost stories satisfyingly allowed for revenge of the dead on their murderers or those that did them a bad turn. Pop culture strongly influenced our ideas of the supernatural, as they continue to do today.

The 19th century saw the rise of spiritualism where ghosts became personally useful to us and we brought them forth in séances as entertainment and as assurances regarding life after death. Also common were “ghosts of the living” which showed that ghosts didn’t even have to be dead but could be strange projections of living people or doppelgängers.

The Society of Psychical Research (SPR) was formed in 1882 in England. This was a group of professional, scientific men who were optimistic that, with rigorous study, life after death could be proven true. Clarke says that in the late Victorian period, when scientists were confident that such evidence was just in reach, belief in ghosts was almost respectable. But the evidence didn’t pan out. It was not convincing to most naturalists. That did not quell popular belief. World War I brought to light the idea of “crisis apparitions”- a vision of a loved one, friend, or even acquaintance that preceded news of trouble or their demise. After the world wars, once again, people sought comfort in the idea of life after death by attempting to connect with their fallen kin. It almost didn't matter how hoaky it was if you really believed.

In the 1930s, the supernatural became the “paranormal” and made appearances in the laboratory of people like JB Rhine who studied ESP. This science-based physicality of the ghost signaled the rise of the noisy ghost or poltergeist. It could be hard to distinguish between a haunting and a poltergeist situation. Some researchers thought poltergeist phenomena was a projection of the mind of certain people, often adolescents and women. Investigators had collected vast amounts of data but it still was not robust enough or fit with a coherent model to explain the phenomena. Ghosts ceased to be souls of the dead roaming the earth, but had now become “emotional fields”.

By the mid twentieth century, we see a very different form of popular ghost than the white-sheeted, chain-rattling, in your face, full-bodied phantom. The study of ghosts became somewhat popular and democratized. You could get a degree as a parapsychologist but you could also claim to be “sensitive” and simply make up ideas about ghosts and write eyewitness accounts as “real ghost stories”. Media savvy characters like Harry Price in the UK sold their tall tales on ghost hunting.

Ghosts had come to America with the Founding Fathers, Clark assures me. American horror writers like Poe and Irving popularized spooky stories. America didn’t have the history and folklore of Europe and Asia where ghosts already thrived. That would change as people like ghost hunter Hanz Holzer decided that our modern intrusion upon ancient native burial grounds disturbed the spirits and caused paranormal activity. Clarke calls this familiar trope (used in the infamous Amityville Horror tale (1977) and basis for the movie Poltergeist (1982)) a “guilt trip” in relation to plundering of Native lands. The idea has no other basis except to serve as a nifty dramatic ploy. Now it seems so self-evident.

Speaking of having no basis in reality, we must address ghost communication, namely EVPs or recorded ghost voices. Ghosts don’t have vocal chords so they have to manipulate electromagnetic fields and imprint their speech (typically extremely terse and often nonsensical) onto the recording device. I asked Clarke what he thought of EVPs and the modern claim that it is some of the “best” evidence for today’s haunted locations.

At points in time, each used to be an accepted idea of what a ghosts was. Since there is no scientific explanation for what people call a ghost, we can’t measure them (contrary to what the Go-go-gadget-wielding paranormal investigators say). A “ghost” is very much at the whim of cultural trends. “Ghost” has no good definition: it’s fluid and we humans can’t seem to pin the darn things down.

> Ghost FAQ: Facts and Fiction

Clarke relates that the medieval ghosts were moral harbingers. They warned the unfortunate victim of the haunt to mend their ways. The purposeful ghost of this type, Clarke says, is an “archaic model from Roman literature and ancient Greece”. The ghost was angry that traditional funerary rites were not conducted. The body of the ghost could be vaporous or lifelike with visible wounds of their death. (See Finucane, 1996)

In the 17th century, ghosts were thought to have been conjured by witchcraft; they were simulacra or demons masquerading as a former human. What goes around comes around, as we see this concept reappear in 21st century pop culture.

Back before television and camera phones, ghosts were described in dramatic accounts as full body apparitions that might be seen at noon as well as midnight. You didn’t have to wait until 3AM, the “devil’s” hour, or "go dark" to spot them. The famous Borley Rectory ghost, the nun, had her own "walk" where you could wait to see her appear at dusk.

In literature and the theatre, the ghost was handy to tell important aspects of the story. Clarke notes that in the 18th century, ghosts came around with something important to say about lost property or hidden wills. The classic Dickens’ ghost serves as a critical plot device and influenced our ideas about ghosts for a very long time as well as did Gothic fiction of MR James and Henry James.

Over and over appears the trope of the ghost who points to the location of his or her unceremoniously dumped remains. Ghost stories satisfyingly allowed for revenge of the dead on their murderers or those that did them a bad turn. Pop culture strongly influenced our ideas of the supernatural, as they continue to do today.

The 19th century saw the rise of spiritualism where ghosts became personally useful to us and we brought them forth in séances as entertainment and as assurances regarding life after death. Also common were “ghosts of the living” which showed that ghosts didn’t even have to be dead but could be strange projections of living people or doppelgängers.

The Society of Psychical Research (SPR) was formed in 1882 in England. This was a group of professional, scientific men who were optimistic that, with rigorous study, life after death could be proven true. Clarke says that in the late Victorian period, when scientists were confident that such evidence was just in reach, belief in ghosts was almost respectable. But the evidence didn’t pan out. It was not convincing to most naturalists. That did not quell popular belief. World War I brought to light the idea of “crisis apparitions”- a vision of a loved one, friend, or even acquaintance that preceded news of trouble or their demise. After the world wars, once again, people sought comfort in the idea of life after death by attempting to connect with their fallen kin. It almost didn't matter how hoaky it was if you really believed.

In the 1930s, the supernatural became the “paranormal” and made appearances in the laboratory of people like JB Rhine who studied ESP. This science-based physicality of the ghost signaled the rise of the noisy ghost or poltergeist. It could be hard to distinguish between a haunting and a poltergeist situation. Some researchers thought poltergeist phenomena was a projection of the mind of certain people, often adolescents and women. Investigators had collected vast amounts of data but it still was not robust enough or fit with a coherent model to explain the phenomena. Ghosts ceased to be souls of the dead roaming the earth, but had now become “emotional fields”.

By the mid twentieth century, we see a very different form of popular ghost than the white-sheeted, chain-rattling, in your face, full-bodied phantom. The study of ghosts became somewhat popular and democratized. You could get a degree as a parapsychologist but you could also claim to be “sensitive” and simply make up ideas about ghosts and write eyewitness accounts as “real ghost stories”. Media savvy characters like Harry Price in the UK sold their tall tales on ghost hunting.

Ghosts had come to America with the Founding Fathers, Clark assures me. American horror writers like Poe and Irving popularized spooky stories. America didn’t have the history and folklore of Europe and Asia where ghosts already thrived. That would change as people like ghost hunter Hanz Holzer decided that our modern intrusion upon ancient native burial grounds disturbed the spirits and caused paranormal activity. Clarke calls this familiar trope (used in the infamous Amityville Horror tale (1977) and basis for the movie Poltergeist (1982)) a “guilt trip” in relation to plundering of Native lands. The idea has no other basis except to serve as a nifty dramatic ploy. Now it seems so self-evident.

Speaking of having no basis in reality, we must address ghost communication, namely EVPs or recorded ghost voices. Ghosts don’t have vocal chords so they have to manipulate electromagnetic fields and imprint their speech (typically extremely terse and often nonsensical) onto the recording device. I asked Clarke what he thought of EVPs and the modern claim that it is some of the “best” evidence for today’s haunted locations.

It surprises my American friends when I tell them that EVP is mostly used in the US despite its European origin. I blame the techno-ghostly aftermath of JB Rhine for the US obsession with ghost hunting technology, a technology which appears to have very little merit. Personally, I can NEVER hear the words and sentences others tell are there.

Me neither.

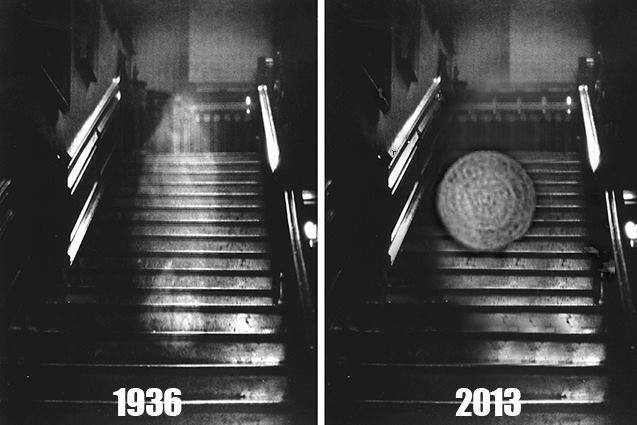

Once upon a time, ghost photos were of filmy, transparent figures with a human form, if sometimes grotesque. But now, we have orbs. Color me unimpressed. Orbs, said to represent spirit energy traveling in its most efficient form – a ball - are a fashion that has passed. “Even the hostess of the British show ‘Most Haunted’ [one of the TV shows that sparked the 21st century ghost hunter popularity] has abandoned the idea, which is saying something,” quips Clarke. Indeed orbs have been clearly explained - most commonly as water vapor, dust, or insects. It’s even suggested that today’s desperate paranormal seekers carry spray bottles with them when the environment feels spooky and they are compelled to take a flash photograph.

Compared to the days of the SPR, today’s paranormal investigators are a sorry lot, attributing every anomaly in digital photos, video, noises, or odd happenings as paranormal phenomena. They bumble around abandoned buildings or historic mansions hunting for “unexplained” happenings. Ghosts are vague mists, temperature changes, EMF spikes , random glitches on a recording, or simply a “feeling”. Hoaxes remain rampant as they always have been, but now there is the internet to distribute and exaggerate them. Oh how the mighty spirit entities have diminished through time.

Once upon a time, ghost photos were of filmy, transparent figures with a human form, if sometimes grotesque. But now, we have orbs. Color me unimpressed. Orbs, said to represent spirit energy traveling in its most efficient form – a ball - are a fashion that has passed. “Even the hostess of the British show ‘Most Haunted’ [one of the TV shows that sparked the 21st century ghost hunter popularity] has abandoned the idea, which is saying something,” quips Clarke. Indeed orbs have been clearly explained - most commonly as water vapor, dust, or insects. It’s even suggested that today’s desperate paranormal seekers carry spray bottles with them when the environment feels spooky and they are compelled to take a flash photograph.

Compared to the days of the SPR, today’s paranormal investigators are a sorry lot, attributing every anomaly in digital photos, video, noises, or odd happenings as paranormal phenomena. They bumble around abandoned buildings or historic mansions hunting for “unexplained” happenings. Ghosts are vague mists, temperature changes, EMF spikes , random glitches on a recording, or simply a “feeling”. Hoaxes remain rampant as they always have been, but now there is the internet to distribute and exaggerate them. Oh how the mighty spirit entities have diminished through time.

Oooh, spooky. Photo Credit: Alexander Ray, Independent Paranormal Researchers Watford, U.K.

Oooh, spooky. Photo Credit: Alexander Ray, Independent Paranormal Researchers Watford, U.K. I could get a bit flustered over the thought of a headless soldier, a phantom nun, or a ghostly carriage crossing the lanes of the dark countryside. But I fail to be moved by a vague mist (that looks oddly like breath condensation) in a photograph. Or worse, an overexposed camera strap hanging in the picture that the enthusiastic believer will call “a vortex”.

Today’s TV ghost shows add to the disrespectability of ghosts. In his book, Clarke refers to them as having a “classless, speedy, problem-solving quality that appeals to the modern mind,“ but they are entertainment, sham investigations, not scientific or even reasonable.

Notice that ghost shows have trended towards including more demonic explanations as we’ve become sensitized to the plain old traditional haunt. Demons are certainly scarier. Hollywood has made sure that we envision demons and possession as horrific with the ability to affect even the innocent kid next door. Sadly, the audience of such horror flicks internalize the idea of demons as plausible so we see not just claims of haunted houses but of portals to hell in the mainstream media. Such “news” stories certainly get attention from both those who believe it or mock it.

Modern ghost hunting is done almost exclusively by amateurs who are just interested in the subject or have had unexplained experiences that made them curious. They are passionate and well-meaning (mostly) but scientifically clueless, playing pretend scientist, and gaining a sense of importance by doing something that feels challenging and unique. (Banishing demons! Whoa!)

Ghost hunts today are a form of wish fulfillment for many. The ghost again plays a role set by the person – an abandoned child, a murdered wife, a lost soldier who repeats his final moments. We seek meaning and fulfillment via roles we assign to the ghost. Once again, we give the ghosts a purpose of our own making.

> Check out Roger Clarke’s Ghosts: A Natural History: 500 Years of Searching for Proof, the 2014 version.

Today’s TV ghost shows add to the disrespectability of ghosts. In his book, Clarke refers to them as having a “classless, speedy, problem-solving quality that appeals to the modern mind,“ but they are entertainment, sham investigations, not scientific or even reasonable.

Notice that ghost shows have trended towards including more demonic explanations as we’ve become sensitized to the plain old traditional haunt. Demons are certainly scarier. Hollywood has made sure that we envision demons and possession as horrific with the ability to affect even the innocent kid next door. Sadly, the audience of such horror flicks internalize the idea of demons as plausible so we see not just claims of haunted houses but of portals to hell in the mainstream media. Such “news” stories certainly get attention from both those who believe it or mock it.

Modern ghost hunting is done almost exclusively by amateurs who are just interested in the subject or have had unexplained experiences that made them curious. They are passionate and well-meaning (mostly) but scientifically clueless, playing pretend scientist, and gaining a sense of importance by doing something that feels challenging and unique. (Banishing demons! Whoa!)

Ghost hunts today are a form of wish fulfillment for many. The ghost again plays a role set by the person – an abandoned child, a murdered wife, a lost soldier who repeats his final moments. We seek meaning and fulfillment via roles we assign to the ghost. Once again, we give the ghosts a purpose of our own making.

> Check out Roger Clarke’s Ghosts: A Natural History: 500 Years of Searching for Proof, the 2014 version.

Sharon Hill, P.G., EdM, is a geologist with a specialty in science and society and public outreach for science. She is the creator and editor of the unique critical thinking blog DoubtfulNews.com and researches, writes and speaks about the paranormal, monsters and natural phenomena for various publications including Skeptical Inquirer and Fortean Times. Follow her on Twitter @idoubtit.