By Sharon Hill

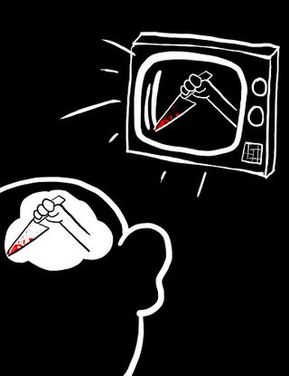

Does violence in movies, television and video games correlate to increased violence and homicide rates? Some people would like you to assume that they do. It’s an easy scapegoat to blame the media for societal ills. But as we often see with social issues, I think you’ll find things are a bit more complicated than that… (Source)

Dr. Christopher J. Ferguson has published a two-pronged study in the 5 Nov 2014 issue of Journal of Communication (DOI: 10.1111/jcom.12129) to address the question “Does Media Violence Predict Societal Violence?” The answer is, he concludes, “It Depends on What You Look at and When”.

In the introduction of the journal article, Ferguson outlines the pitfalls in the still-raging debate about media as a contributing factor to violence. The American Psychological Association put out a policy statement in 2005 linking media violence to societal aggression. But a backlash of other researchers resulted in a request for the APA to review their policy because there is not a consensus among scholars (an ACTUAL scientific controversy).

In what appears to be “common sense”, we notice an increase in violence on television and in movies and tend to associate it with news stories about youth violence or mass shootings especially when the news media emphases a suspect's connection with such media. Video games in particular have notably evolved to show more realistic and graphic depictions of war, criminal violence, and horror scenes. It seems all too easy to blame new media for the increase in mass shootings or heinous crimes. And it is too easy; that is not the whole story.

Does violence in movies, television and video games correlate to increased violence and homicide rates? Some people would like you to assume that they do. It’s an easy scapegoat to blame the media for societal ills. But as we often see with social issues, I think you’ll find things are a bit more complicated than that… (Source)

Dr. Christopher J. Ferguson has published a two-pronged study in the 5 Nov 2014 issue of Journal of Communication (DOI: 10.1111/jcom.12129) to address the question “Does Media Violence Predict Societal Violence?” The answer is, he concludes, “It Depends on What You Look at and When”.

In the introduction of the journal article, Ferguson outlines the pitfalls in the still-raging debate about media as a contributing factor to violence. The American Psychological Association put out a policy statement in 2005 linking media violence to societal aggression. But a backlash of other researchers resulted in a request for the APA to review their policy because there is not a consensus among scholars (an ACTUAL scientific controversy).

In what appears to be “common sense”, we notice an increase in violence on television and in movies and tend to associate it with news stories about youth violence or mass shootings especially when the news media emphases a suspect's connection with such media. Video games in particular have notably evolved to show more realistic and graphic depictions of war, criminal violence, and horror scenes. It seems all too easy to blame new media for the increase in mass shootings or heinous crimes. And it is too easy; that is not the whole story.

I found Ferguson’s quote in a press release particularly pithy and illustrative of a concept I feel strongly about as well:

"Society has a limited amount of resources and attention to devote to the problem of reducing crime. There is a risk that identifying the wrong problem, such as media violence, may distract society from more pressing concerns such as poverty, education and vocational disparities and mental health. This research may help society focus on issues that really matter and avoid devoting unnecessary resources to the pursuit of moral agendas with little practical value.”

"Little practical value" put me immediately in mind of the huge effort by law enforcement to ferret out nonexistent Satanic cults in the 80s and 90s. Recently, I finished reading Bill Ellis’ Raising the Devil (2000) chronicling the incorporation of ideas of demonic possession as the root of individual human problems by Charismatic Christians. The perception of the devil's influence eventually turned into a raging societal problem involving lurid tales of Satanic cults and ritual abuse of women and children. The Satanic Panic is solidly regarded as being a multi-factorial issue that could NOT be linked to any actual underground network of orgies and blood sacrifices. It gained credence from a now discredited method used by psychotherapists to “recover memories”. It also highlighted the legal problems of coercing testimony from children that turned out to be imaginary and highly embellished but taken at face value. The Satanic Panic was a moral agenda that landed several innocent people in jail, ripped families apart, and resulted in tremendous trauma for victims (not of Satanic abuse, but of careless counselors, religious figures and municipal officials).

Through its rise, the idea of underground Satanism was heavily sensationalized in the media. Ellis cites Hammer Studio films as latching onto concepts about Black Magic for dramatic effect in their productions. The movies exploited symbols and rituals of the devil. Eventually, as films pushed the limits of the ethical codes, the genre evolved into grisly displays of bloodshed, gore and torture. The Hammer horrors were the precursors to the “splatter” films that were popular with adolescents and young adults from the 1960s onwards to the modern “torture porn” and special effects extravaganza horror. Such movies may influence the public into thinking that secret demonic traditions are practiced and that deviant violence of this nature is really going on out there, it’s just covered up. How much of this perception is a result of the availability heuristic is not clear but exposure does provide an introduction, perhaps desensitization to violence, and plants the seed that something that awful might hold a grain of truth.

Ferguson’s research looked at the macrolevel trends in patterns of programing and changes in cultural believes, a different approach than in the past. Most of the previous research into the correlation of violent content to behavior was done in the lab, asking participants to view short clips and then measuring their reaction. That is not exactly reflective of real life where consumers may binge-view hours of Game of Thrones, have a horror movie marathon, or playing Grand Theft Auto or Manhunt (banned in several countries for its graphicness) for the entire night.

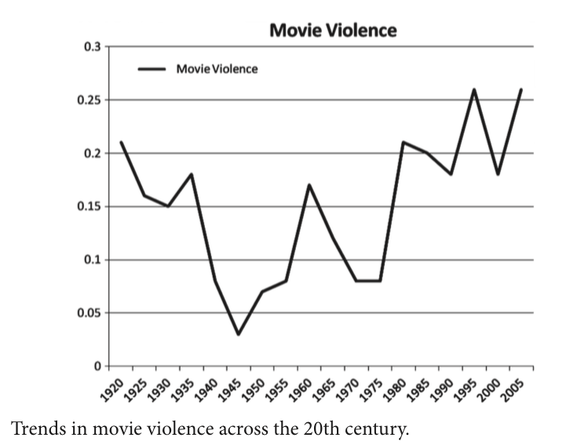

Ferguson used data from the Cultural Indicators project to “make inferences about the potential impact of television programming on issues related to fear of crime, alienation and insecurity, and other aspects of social reality.” His first study compared relations between movie violence and homicide rates in the U.S. in the 20th century.

Results showed that the trend toward more graphic and violent content did not correlate with societal violence but the frequency of violence in movies did correlate to homicides. But the correlation was small and the trend reversed itself later in the 20th century. The correlation also diminished when other factors were controlled such as those relating to economic conditions.

Through its rise, the idea of underground Satanism was heavily sensationalized in the media. Ellis cites Hammer Studio films as latching onto concepts about Black Magic for dramatic effect in their productions. The movies exploited symbols and rituals of the devil. Eventually, as films pushed the limits of the ethical codes, the genre evolved into grisly displays of bloodshed, gore and torture. The Hammer horrors were the precursors to the “splatter” films that were popular with adolescents and young adults from the 1960s onwards to the modern “torture porn” and special effects extravaganza horror. Such movies may influence the public into thinking that secret demonic traditions are practiced and that deviant violence of this nature is really going on out there, it’s just covered up. How much of this perception is a result of the availability heuristic is not clear but exposure does provide an introduction, perhaps desensitization to violence, and plants the seed that something that awful might hold a grain of truth.

Ferguson’s research looked at the macrolevel trends in patterns of programing and changes in cultural believes, a different approach than in the past. Most of the previous research into the correlation of violent content to behavior was done in the lab, asking participants to view short clips and then measuring their reaction. That is not exactly reflective of real life where consumers may binge-view hours of Game of Thrones, have a horror movie marathon, or playing Grand Theft Auto or Manhunt (banned in several countries for its graphicness) for the entire night.

Ferguson used data from the Cultural Indicators project to “make inferences about the potential impact of television programming on issues related to fear of crime, alienation and insecurity, and other aspects of social reality.” His first study compared relations between movie violence and homicide rates in the U.S. in the 20th century.

Results showed that the trend toward more graphic and violent content did not correlate with societal violence but the frequency of violence in movies did correlate to homicides. But the correlation was small and the trend reversed itself later in the 20th century. The correlation also diminished when other factors were controlled such as those relating to economic conditions.

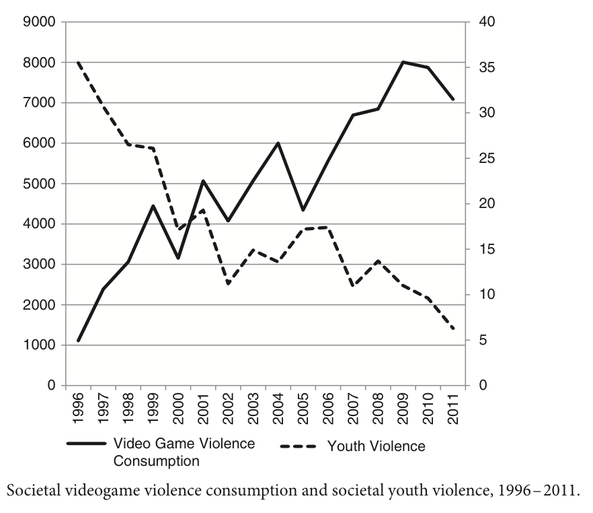

The second study tested the hypothesis about video game violence associated with rates of youth violence. IMDB (the Internet Movie Database) was used to gather information about video game content and sales, focusing on those with violent themes using the ESRB ratings (T for Teen, M for Mature, etc.). Violent games were among the most popular sellers in most years of the study period. The result was quite the opposite of what might be expected by parental “common sense” - the data showed a strong inverse relationship between violent games and documented violence in society.

Obviously, correlation (or lack of it) does not imply causation. But the results do demolish the trope that media violence breeds societal violence. Is the answer clear cut? No. Social issues hardly ever are - people, culture and society is incredibly complicated with so many moving pieces and influences at work. To simply blame the media implies that the audience is passive, not able to make personal judgments, and overwhelmingly influenced by one factor at the expense of many other individual factors. For religious leaders and watchdog groups to point blame at the media clearly is overly simplistic, naive, and insulting to the audience who consumes this media for their own personal and various purposes. But such acts of identifying the "enemy" do serve interesting purposes.

I asked Dr. Ferguson his thoughts on comparing the moral agenda focused on violent media to that of the fear of Satanic ritual abuse and cults:

I asked Dr. Ferguson his thoughts on comparing the moral agenda focused on violent media to that of the fear of Satanic ritual abuse and cults:

[Moral panics] can serve to give a kind of shared moral focus onto a perceived problem. Everybody hates Satanic Ritual Abuse, for instance, and coming together in fear of such a "false epidemic" can give us a sense of shared moral ground.”

It’s nothing new, either. The act of lamenting youth behavior might be as old as human society itself. Dr. Ferguson continues:

“Repugnance toward new forms of media, whether jazz, comic books, TV, rock music, video games, etc., can fulfill the same purpose [of shared moral focus], particularly involving older members of society coming together in a shared sense of losing control of society to an out-of-control youth.”

Ferguson's paper contains much more insightful information about the studies and background and is available to access at the Journal of Communication site. It ends with a section on social implications describing how the research should inform policy decisions. It is noted is that moral panics can draw too much attention to culture war issues (easy targets) instead of tackling the extremely difficult to solve social problems, like poverty and poor education, that require planning, time, political will, and great financial investment.

Ferguson cites a source that documented that news coverage of media violence has become more skeptical in recent years. That is good news. Are people realizing that you can’t just lazily blame the media for all our social problems?

Yet, an incentive remains to feed them, Ferguson cautions. “Scholars get grant money to study the problem, politicians can rail against a moral evil, journalists get headlines, page clicks, etc.” The monster of misperception grows.

If we wish to truly better society, the approach must not be one of scapegoating a single, possibly erroneous cause, but to draw experts in from the multiple fields to help parse out a very complicated, nuanced issue in a multi-disciplinary framework. We are awash with media influence and bombarded with messages from outspoken critics who want to highlight their moral agenda by demonizing violent movies, television, video games, heavy metal or hip hop music, or certain subcutures and religious groups. That way, the headlines are much shorter and more sensational. The real world is only explained via a far more complicated equation.

Dr. Christopher Ferguson of Stetson University also wrote a series of essays for time.com and is author or co-author of three books.

Ferguson cites a source that documented that news coverage of media violence has become more skeptical in recent years. That is good news. Are people realizing that you can’t just lazily blame the media for all our social problems?

Yet, an incentive remains to feed them, Ferguson cautions. “Scholars get grant money to study the problem, politicians can rail against a moral evil, journalists get headlines, page clicks, etc.” The monster of misperception grows.

If we wish to truly better society, the approach must not be one of scapegoating a single, possibly erroneous cause, but to draw experts in from the multiple fields to help parse out a very complicated, nuanced issue in a multi-disciplinary framework. We are awash with media influence and bombarded with messages from outspoken critics who want to highlight their moral agenda by demonizing violent movies, television, video games, heavy metal or hip hop music, or certain subcutures and religious groups. That way, the headlines are much shorter and more sensational. The real world is only explained via a far more complicated equation.

Dr. Christopher Ferguson of Stetson University also wrote a series of essays for time.com and is author or co-author of three books.

Sharon Hill, P.G., EdM, is a geologist with a specialty in science and society and public outreach for science. She is the creator and editor of the unique critical thinking blog DoubtfulNews.com and researches, writes and speaks about the paranormal, monsters and natural phenomena for various publications including Skeptical Inquirer and Fortean Times. Follow her on Twitter @idoubtit.